Closer to the heart: Eliminating barriers to heart health for African Americans

February 03, 2020

This month being both Black History Month and American Heart Month we are shining a spotlight on heart health among African Americans. Statistics show that African Americans are 150% more likely to suffer from high blood pressure than the general population, putting them at higher risk for a host of health conditions, including heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease. The medical community suspects that genetic, environmental, and social factors are at play.

Several professors at NYU Meyers are looking for more nuanced explanations and treatments for this troubling health disparity. In this article we explore the research of Profs. Sandy Cayo and Maya Clark-Cutaia.

Why discrimination and stress can damage the heart

Prof. Sandy Cayo studies cardiovascular health among African American women. In particular, she looks at how psychosocial factors — such as perceived discrimination, stress, and depression — impact their blood pressure. Left unchecked, high blood pressure can lead to serious health problems, including heart disease, kidney disease, and stroke.

“One of the most crucial areas of health for black women is cardiovascular health,” says Cayo. Today, nearly 48% of African American women have some form of cardiovascular disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control. At the same time, they are less likely to get the life-saving medical care they need.

While science has long understood the link between stress and elevated blood pressure, Cayo is looking at more chronic and insidious sources of stress, including perceived racial discrimination from the patient perspective.

“The background context of my work focuses on implicit and unconscious bias among healthcare providers and how that impacts delivery of equitable care,” says Cayo. “For example, if I feel like I’m being discriminated against by a provider or have had a lifetime of experiences with discrimination, that can influence how I may cope with stressors overall. That stress, coupled with things like depression, can influence how I care for myself.”

Cayo’s primary data source is the famed Jackson Heart Study. Started in 1998 and including over 5,300 participants from the Jackson, Miss., metropolitan area, it is the largest single-site, community-based investigation into environmental and genetic factors associated with cardiovascular disease among African Americans ever undertaken. Its goal is to identify the reasons for the greater prevalence of cardiovascular disease among African Americans and to uncover new approaches for reducing this health disparity.

What is unique about the Jackson Heart Study – and key to Cayo’s research – is that participants were tested not just for their blood pressure and pulmonary functions, but also their levels of stress, exposure to violence, depression levels, and perceptions of discrimination.

As Cayo explains, “There are gaps in care when you have providers who have biases. The literature shows, you’ll have an African American patient who presents with the exact same cardiac symptoms as a white patient, and providers, both African American and Caucasian alike, will aggressively treat the white patient and will not aggressively treat the black patient because of predetermined notions of the black patient not being compliant with their medications, care, or follow-up.”

In a troubling 2007 study, researchers followed emergency room physicians in Atlanta and Boston who were treating patients with chest pains. Testing showed physicians with implicit stereotypes saw black Americans as "less cooperative with medical procedures and less cooperative generally.” The more biased the physician, the less likely they were to treat black patients with thrombolysism, a potentially life-saving care.

In a troubling 2007 study, researchers followed emergency room physicians in Atlanta and Boston who were treating patients with chest pains. Testing showed physicians with implicit stereotypes saw black Americans as "less cooperative with medical procedures and less cooperative generally.” The more biased the physician, the less likely they were to treat black patients with thrombolysism, a potentially life-saving care.

“Uncovering the bias part is difficult. You won’t get [providers] upfront saying, ‘Yes, I’m biased and I also deleteriously impact care because of my biases.’ They’re not going to say that. So I go by evidence and literature and what the state of the science is on implicit and unconscious bias,” explains Cayo.

It goes without saying that the effects of bias on patients are profound, impacting their quality of care, overall quality of life, and even survival rates. But where Cayo sees potential explanations in psychosocial factors of health, she also sees possible solutions.

“Some of these psychosocial factors you can prevent. Like discrimination, how we can prevent that? By addressing bias among providers throughout the healthcare system, which includes physicians, nurses, ancillary staff, and administrators. We must also address institutional and systemic racism, because those hierarchies have huge implications on the care progression of patients,” emphasizes Cayo.

In July, Cayo will present research findings at the National Black Nurses Association on neighborhood violence and crime and their relationship to cardiovascular disease.

“For those who are unable to advocate for themselves, those who are marginalized and underserved, and those who are most vulnerable, their cause is my life’s work,” says Cayo.

Heart your kidneys

"We talk about our families, things that are going on . . . It really makes me want to get an answer for them, because that could be my uncle, my brother, my mom, my cousin." - Prof. Maya Clark-Cutaia.

Prof. Maya Clark-Cutaia works on a condition that closely tracks heart health — kidney disease. Her patients often live with multiple chronic conditions, including kidney disease, diabetes, and heart disease, at the same time.

“Kidney disease is one of those disease processes that is associated with diabetes and high blood pressure,” she explains. It has been termed a “disease multiplier.” Almost 50% of individuals with chronic kidney disease also have diabetes and cardiovascular disease. “In all three disease processes, minorities are overrepresented, so the majority of my patients are African American.”

If patients do not manage their end-stage renal disease well, then excess fluids in the body can back up into their heart, causing a range of problems — from difficulty breathing and shortness of breath to chest pain, heart attacks, and an enlarged heart. At the same time, high blood pressure is often one of the main causes of end-stage renal disease.

If patients do not manage their end-stage renal disease well, then excess fluids in the body can back up into their heart, causing a range of problems — from difficulty breathing and shortness of breath to chest pain, heart attacks, and an enlarged heart. At the same time, high blood pressure is often one of the main causes of end-stage renal disease.

Explains Clark-Cutaia, “It’s a vicious cycle of cardiac issues.”

According to government statistics, African Americans are 370% more likely to develop end-stage renal disease — as well as all of the attending complications and comorbidities that go along with it.

Most of Clark-Cutaia’s work focuses on educating patients so that they know their disease process, develop a workable management plan, and understand how it impacts both their quality of life and prognosis.

Changes in diet and lifestyle are universally recommended parts of a treatment plan for end-stage renal disease. One of the main interventions is limiting the amount of salt that patients consume. Based on Clark-Cutaia’s NIH/NINR-funded career development award, she has learned that “there is definitely something around the 2,000-mg-of-sodium-a-day that seems to reduce fluid gains between dialysis sessions.”

However, meeting tight dietary restrictions can pose particular challenges for this patient population — who often face additional socioeconomic burdens.

“It’s almost impossible for us to eat the way that we’re supposed to eat with a certain amount of income and means. My patients are typically people who live in low socioeconomic neighborhoods that don’t have grocery stores, they’re on federal subsidies, so they can’t afford to do fresh fruits and fresh meat,” says Clark-Cutaia.

“There are a bunch of mom-and-pop shops and gas stations that accept food stamps and EBT cards and things, so that’s where they go. That’s where they grocery shop.”

For Clark-Cutaia, finding treatments that work is about meeting patients where they are.

“Even though I grew up in Germany, my parents are very southern. There’s a lot of sodium in what we eat.” As she points out, not all people eat the same, an issue that physicians, nurses, and other care providers need to be attentive to when working with diverse patient populations.

“I understand what some of that psychosocial world is like, which makes the research process a bit easier. But it also really makes me want to get an answer for them, because that could be my uncle, my brother, my mom, my cousin.”

Another contributing factor is that African Americans tend to be diagnosed with kidney issues later in their disease development, when symptoms are more difficult to manage — leading to higher risks of cardiovascular disease and heart failure. This could be the result of several factors, including lack of access to healthcare or even, as some charge, a kidney scoring system that is inherently discriminatory.

For the past 20 years, the medical community has relied on different diagnostic criteria for kidney disease in black patients than in the rest of the population. Clinicians and researchers have started questioning that scoring system, which some say is contributing to poorer outcomes for black and mixed-race patients. “People are saying, maybe we should just take this out and have everyone be assessed with the same criteria.”

At the same time, African Americans face additional barriers to accessing industry-standard, life-saving treatments for kidney disease, which would at the same time help prevent heart attacks and cardiovascular disease. The ideal situation for someone on dialysis would be getting a new kidney, but African Americans and other minority patients are less likely to sign up for organ transplants. “There is a lot of research that suggests that it’s related to lack of trust, religion, health literacy . . . There’s some research coming out now that suggests that it’s not even really being discussed with them.”

Clark-Cutaia is looking for larger solutions to help patients manage their often multiple and complex disease burdens. She is applying for a grant that would test a new food-delivery system for patients, where they would receive free, medically tailored meals through their insurance.

Clark-Cutaia is looking for larger solutions to help patients manage their often multiple and complex disease burdens. She is applying for a grant that would test a new food-delivery system for patients, where they would receive free, medically tailored meals through their insurance.

The study, which would be piloted in Philadelphia, may also include a final phase that trains patients in how to prepare the specialized meals themselves.

“It needs to be bigger than me just telling patients to reduce their sodium,” says Clark-Cutaia. “I can’t imagine managing all of the appointments, dialysis, and medications. They have families. Some have jobs. It’s a lot . . . So what things can we do to reduce their risk, while making it accessible in the community? How can we put fewer constraints and responsibilities on them?”

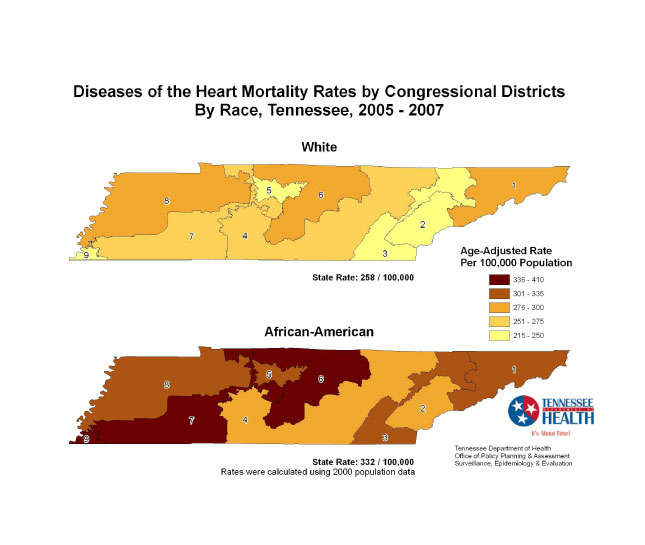

Photo captions: Exercising at a Get Fit and Tone Class, in Canton, MS (Courtesy of the Jackson Heart Study); infographic revealing the disparity in heart mortality rates, Tennessee Department of Health, Office of Policy, Planning and Assessment of surveilance, Epidemiology, and Evaluation (Centers for Disease Control); graphic developed for Prof. Clark-Cutaia's study on kidney-heart health; "Convenience" (Lee Edwin Courser, flickr); "Wal-Mart Neighborhood Market grand opening 01162013 056" (Public Information Office, Marietta, GA, flickr); "Salad bar" (National Institutes of Health).