COVID-19: To support vulnerable populations, we need to ask difficult questions

April 29, 2020

By Prof. Maya Clark-Cutaia, Assistant Professor of Nursing

“The advent of COVID-19 has not only highlighted existing disparities and inequities, it has reminded us of the significantly poorer outcomes related to lack of resources in vulnerable communities.”

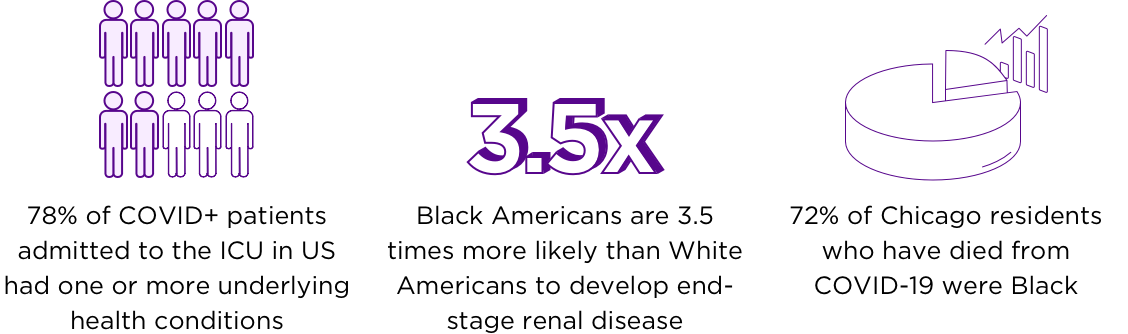

Individuals suffering from underlying medical conditions, in particular those with multiple chronic conditions, such as heart disease, obesity, and kidney disease, are at increased risk of a COVID-19 diagnosis and COVID-related mortality. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 78% of COVID+ patients admitted to the ICU in the United States had one or more underlying health conditions. These individuals are often from vulnerable populations — the elderly, the immunocompromised, the institutionalized, and the disenfranchised.

In particular, Black and Brown communities, which suffer much higher rates of chronic conditions like kidney disease, are more likely to be hospitalized and die as a result of COVID-19. In Chicago, for example, 72% of COVID mortality has been in Black residents, yet the city is only 29% Black. This is the population of patients I provide care to and conduct research with. My patients are from minority backgrounds, live in low-socioeconomic status neighborhoods, and have low health literacy. They are the patients with diabetes and hypertension supported by federally subsidized programs, already making decisions regarding their health versus their basic necessities. As such, they are likely to have poorly controlled medical conditions. They are the patients in community hospitals. My patients are also often in nursing homes — however, they could just as easily be in prisons and jails, because the risks and health disparities for these populations are the same. The advent of COVID-19 has not only highlighted existing disparities and inequities, it has reminded us of the significantly poorer outcomes related to lack of resources in these communities. As it emphasizes deadly disparities in underlying medical conditions and treatment regimens in vulnerable populations, it has forced us to take stock of how the current provision and division of healthcare resources in our country contributes to healthcare inequities. Forget the many advantages afforded to those of means, such as testing and homeopathic remedies that may or may not work, the sheer way of life of many of these patient populations puts them at risk of serious illness and not adhering to recommended restrictions and management plans. For example, they have to go to work to make money and they are less likely to seek medical care and more likely to rely on social networks like their church for support. They are the patients who have less ability to tune into CNN, Fox, or MSNBC, and search the web or other news outlets to stay informed of the COVID-19 crisis. For those in prison, tight quarters do not allow for social distancing, leading to dangerously high rates of COVID-19, as in Illinois' Cook County Jail. Furthermore, much needed resources such as medical staff and supplies are limited, and some institutions, depending on location, geography, and funding, for example, are under-resourced. Many of us would like to assign blame. We would like to the prosecute the perpetrator, but the fact of the matter is, these disparities have existed long before COVID 19 and will, sadly, most likely persist after the pandemic. This is not to say that tackling disparities and inequities is hopeless, but that it is time to channel our outrage into action, action that is sustainable, action that is meaningful. We, as providers and researchers, need to be innovative in the ways that we reach our patients and ensure that they have the resources they need to keep themselves healthy and reduce their risk of contracting COVID-19. This includes eating and sleeping well, exercising, taking their medications on time, and adhering to treatment schedules, like dialysis regimens. We need to ask ourselves difficult questions, like: How are vulnerable patients obtaining their medications from the pharmacy? How are those who suffer from kidney disease being transported safely to and from dialysis when they are already immunocompromised? How are we reducing their risk when the suggested personal protective equipment (PPE) is already worn and patients still suffer from line infections, and PPE is at a premium? How are patients consuming the recommended diet when the general population continues to “stock up” during these periods of restriction? What food remains on the shelf that is SNAP or WIC approved? How do you get exercise in a neighborhood that is not safe to walk? And then, we need to come up with creative solutions. Providers need to educate patients and identify at-risk and vulnerable populations as well as their potential needs and how to address them. It is paramount that we facilitate rapports between communities with resources and those without. Policymakers need to broaden the scope of federally subsidized programs. Additionally, it is time to begin to incentivize healthcare professionals to work in these under-resourced areas and institutions. While such programs have existed for rural areas, there are many areas in which underserved, vulnerable populations still require attention. We need to gain a better understanding of the facilitators of the disparities in our nursing homes and develop realistic solutions to bring resources into these facilities. We also need pharmaceutical companies, pharmacies, and health systems to provide medications to patients free of charge and to potentially ensure that prescription refills are delivered to those in need. Local politicians can encourage safe practices to keep their constituents healthy, like crowd control and safe distancing in lines at the grocery store and supporting local food delivery and the other necessary efforts. We need to demand that jails and prisons must institute early-release programs and create optimal management conditions for those caring for this forgotten population. If we fail now to protect these groups from COVID 19, the mortality rate will continue to rise. We will fail to flatten the curve, especially in Black and Brown communities. Each of us will be impacted by the loss of a loved one to this novel illness.

Unequal, unprotected

Plan and provide resources in vulnerable populations

“How are vulnerable patients obtaining their medications from the pharmacy? How are those who suffer from kidney disease being transported safely to and from dialysis when they are already immunocompromised?”