COVID-19: Inside the Disaster Nursing classroom with Prof. Bucco

May 26, 2020

An interview with Prof. Theresa Bucco, Clinical Assistant Professor

Prof. Theresa Bucco teaches Disaster Nursing and Emergency Preparedness, an elective course she created at NYU Meyers in 2018. This week, she won a grant from the NYU Curriculum Development Challenge Fund, which promotes innovative curricular programming across the university, to put the final polish on this high-in-demand course. Only a few nursing schools offer this specialized training for students. In the classroom, Bucco draws from her firsthand experience as an emergency room nurse educator at Staten Island University Hospital, where she has worked for 25 years and still trains over 100 front-line nurses. She has also trained with FEMA at the Center for Disaster Preparedness (CDP) in Anniston, AL.

Do you think your students were at an advantage this spring, studying pandemics during a major pandemic?

Of course. Something I always say to my students, which I learned at the CDP, is — it's not a matter of if a disaster will occur, it's a matter of when. And here we are in the midst of one. Still, I never thought that I would be teaching this course during a major pandemic.

Many of my students never thought that they were going to need their disaster nursing training. Now they are sitting on the precipice of this huge disaster as they graduate. They've got this knowledge, and they want to get out there and use it.

How do you convey the seriousness of disaster nursing without scaring off young students?

I don't want them to be afraid, but I do teach them that they have to be safe. That's one of the important concepts that they have to know. I tell my students, many times you won't know what you're walking into, but you will get used to it and you will survive. For instance, years ago, we didn't know what we were walking into when we were dealing with HIV.

It’s so important that they know how to protect themselves, making sure that they are safe and that they keep their family safe. At the same time, they must provide the best patient care that they can using the appropriate personal protective equipment — which is so important, especially in this pandemic.

I want my students to be brave and safe at the same time.

What are some topics you cover?

I teach them about dressing with PPE, and students get to try on the different levels of PPE. When I taught our PPE class in early March, I wasn't sure what level we would need for COVID-19. Now we know it requires essentially the same PPE as the Ebola virus: the gown, N-95 respirator, gloves, and face shield.

I also showed them the PPE for a chemical disaster and a biological disaster — up to the second-highest level of PPE, not the highest, which we do not have here or in my emergency department. I also dress them in the PAPR, so students know what it's like to be in equipment with air flowing into their hoods. They were surprised. We were lucky to be able to have that class before we moved to remote learning. The students loved it.

For the last two weeks of the course, students gave presentations on past disasters, looking at how it was handled then, the nurse's role then, and how would it be different now. They had to find all of the supporting evidence and historical documents. One student chose the 1918 flu pandemic, another did Chernobyl.

What else is important to learn about nursing during a disaster?

Communication is one of the biggest issues. We studied what has been happening between the White House, the media, and all the people sharing their views. Are they all right? In a disaster, you have to speak with one voice — again that is something I learned at the CDP. There has to be one person who speaks. But now, we see everyone is offering their opinions. When Dr. Anthony Fauci, the President of the United States, and Dr. Deborah Birx are all speaking in the same voice, with the same message, the people understand the message. But what we have is many different people saying different things, leading to confusion.

What are some of the unique challenges this crisis presents?

With a crisis like Superstorm Sandy, the disaster comes and goes, and then we have the aftermath. Here, we have to provide care through a crisis with no endpoint. COVID-19 will be with us for some time.

Another reason is that COVID-19 is so contagious — it's not like any other virus we’ve seen before. Many of these patients are actually dying alone. They are being intubated, the virus is attacking their lungs, they'll survive for a bit on the ventilator, and then there's a point where they just don't. We cannot oxygenate them and the patient actually goes into full-blown cardiac arrest. Also, many times, the families cannot be present because they're not allowed in. But you still have to have phone conversations with them.

“I don't want [my students] to be afraid, but I do teach them that they have to be safe. That's one of the important concepts . . . I want my students to be brave and safe at the same time.”

How did the COVID pandemic change your course?

It changed it drastically. First, we had to move to remote classes in early March, which was a challenge for students as well as myself.

There are also so many points to bring up, it's such a hotbed of information and ethical issues. In April, we did a role-playing exercise on COVID-19 with the Community Health Course, taught by Prof. Stacen Keating. All of my Disaster Nursing students are also in her course. Stacen and I collaborated in developing a COVID medical scenario for students to work through, with an ethical dilemma. They were asked to look at a Ventilator triage patient scenario, imagining themselves as part of an interdisciplinary team where there were five patients and only one ventilator. The physician had to make a choice about who was going to get it. Each student had to decide which patient they thought the physician would choose and why — and also which patient they would advocate for.

This is a totally new type of scenario that was presented because of what's happening with COVID-19 right now in the hospitals. Doctors are making choices about who they will ventilate. We framed the dilemma for students under the guidelines of the physicians, because as nurses, we don't make those decisions. We may be involved in them as part of a collaborative team, but we don't make those decisions.

Who is the average student in your course?

Most are fourth-sequence students. Many have experience as an EMT or patient care assistant — or have worked in the medical reserve corps. Disaster nursing is an alternate route and specialty in nursing. You can be a disaster management specialist at a hospital or corporate group. There are opportunities for growth and development, as the COVID pandemic has again shown.

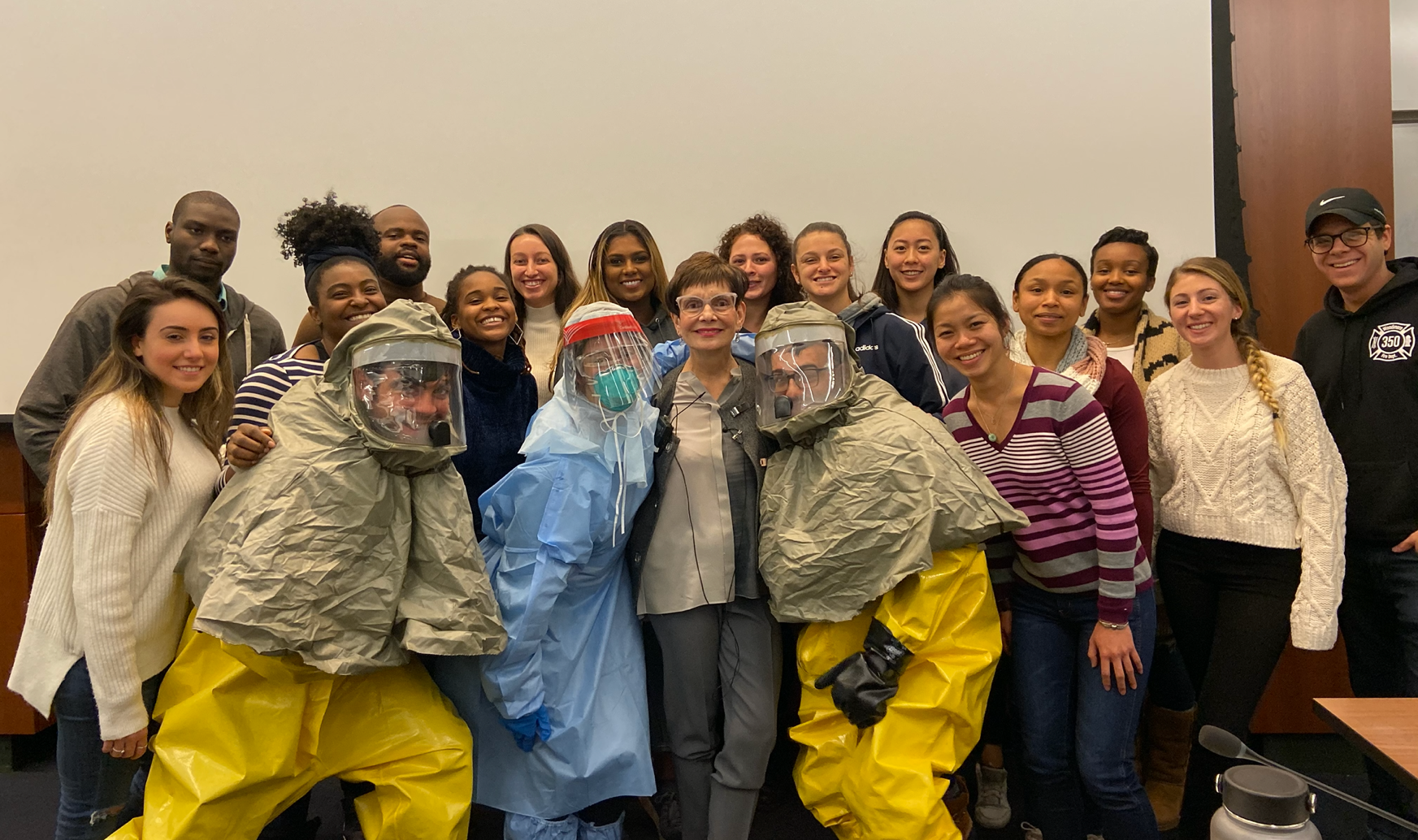

Prof. Bucco with her Spring 2020 class, before they moved to remote instruction.